On the incompleteness of philosophical knowledge and the idea of truth: criticisms and justifications

11.10.2012 00:16

On the incompleteness of philosophical knowledge and the idea of truth: criticisms and justifications

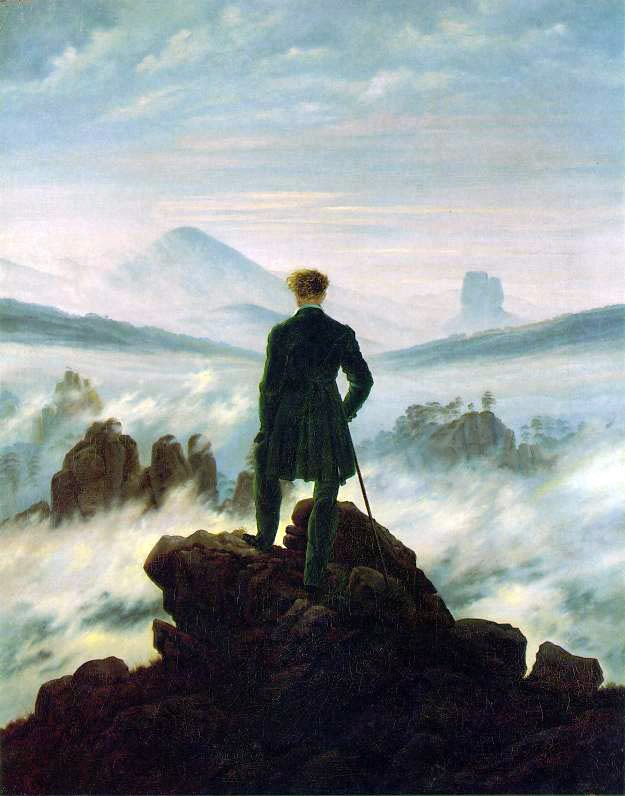

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, Caspar David Friedrich

INTRODUCTION

Friedrich Nietzsche, a great admirer of Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings, stated: “‘Truth is simple’ – Is that not a compound lie?” Philosophers are in a position where they pretend to speak from nowhere and to give a truthful vision of the human being and the world. The condition of the philosopher cannot escape the reliance on truth as the unifying element of its propositions and his or her whole theory. As well as in the painting, the philosopher sees the world from a perspective and has to deal with the question about the incompleteness of philosophical knowledge. In this paper I will assess the concept of truth, within a limited condition, and analyze in which way this idea is the basis for the interpretation of the world that philosophers want to attain.

INCOMPLETENESS

Firstly, we need to evaluate whether human beings can achieve a complete understanding of their nature and of reality. In Friedrich Hegel’s idealism, there was no limit to philosophical knowledge. In fact, for him, all that was rational, and implicitly truth, was also real. “So far… reality has a rational structure.” Hegel thought that mind and reality had the same logical basis in their conception. “The idea is truth in itself and for itself – the absolute unity of concept and objectivity.” Hegel supposed that thought and reality were linked together. In truth, they were of the same nature. This idea gave the possibility to human beings to comprehend an Absolute Reality by understanding the Absolute Idea. In his idealism, Hegel gave the opportunity to comprehend the nature of reality through the view of a holistic structure of logic and thus making the philosopher’s interpretation a search for the ultimate truth.

Bertrand Russell, on the other hand, rejected the belief of an unlimited human knowledge. To do so, Russell introduces the term “nature” which he describes as the “…thing’s relations to all other things in the universe…” This is what is impossible to achieve for human beings and is what will mark the incompleteness of human beings knowledge. Man cannot reach the metaphysical ideal of describing reality as it is in its totality, but only know, throughout, truths, what are some aspects of the definite objects of its composition. He also positioned logic as a “…liberator of the imagination…” , as many of the conclusions produced by logic can contradict common sense. Logic is more as the creator of many possibilities that adjust to reality, rather than an instrument to create truths. Russell concluded that the philosopher needs to accept its limited nature and, thus, to admit that “reality may extend beyond our conceptual reach and that there may be concepts that we could not understand” .

The limitation of the philosopher must be accepted. Hegel’s idea was too pretentious and confused the nature of ideas with that of reality. Every philosopher must approach theories with some degree of humility, and accept that, restrictions are inevitable, otherwise discussion is impossible.

TRUTH

Furthermore, we can agree on our epistemological and metaphysical limitations, but that is only the condition on which we must build our theories as philosophers. We must find now which tools will we use to found or validate a certain theory within all this incompleteness. How are we going to make our ideas valuable if we as human beings are limited? That question will be assessed looking at the different approaches to truth and how this can be a useful tool for the comprehension of that condition, and of reality.

1. Truth is a fundamental component of philosophy in the way that no philosophical conception or system is free from an evaluation of that condition, since it is that very condition what makes a theory or even an argument plausible and valuable. Gilles Deleuze, a French post-structuralist, in his analysis of sense explains the conditions in which truth arises. He states that the base on which truth is created is on the signification and demonstration of a proposition. Signification meant as the “… order of conceptual implication where the proposition under consideration intervenes only as an element of a ‘demonstration’.” Sense arises as a feature of the proposition that defines from the various possible implications what will be the logical order. Therefore, truth is dependent on the extrinsic syntactic implications of the proposition and the signification of other objects of knowledge. Truth is an attribute of a proposition when this has sense in a coherent system of implications. For instance, when we talk about particle physics, we use concepts such as “quarks” that we don’t see but that are intelligible by the whole theory of particle physics. We are considering a type of knowledge that is based on a certain system of propositions that makes valid that specific knowledge. However, if we use those knowledge objects out of the coherent system from which they arise, they become illogical and without sense. Truth, then, is something for a philosopher that is founded in a structural system of sense; it is not something created by the human being, but rather a precondition for human knowledge. Criticism and skepticism towards the epistemological system is categorical, since is the only way to evaluate the interplays and games of truths.

2. Moreover, a current philosophy which tries to define truth is that of analytic philosophy. One of the leading representatives of this group is Bertrand Russell. He constructed a theory of truth based on the condition that truth needs to admit an opposite, falsehood, and that truthfulness and falsehood are properties acquired by propositions or statements based upon the relations they have to other things . Therefore, truth arises when a system is coherent. Truth is the result of an effective relation between a proposition with other propositions, or with reality itself. The statement acquires truthfulness not because its plausibility is intrinsic, but because is related correctly with other elements. However, unlike Deleuze, Russell states that coherence is not always the case when a proposition has to be evaluated as truthful, since there can be many possibilities in the arrangement of a coherent system of propositions. Hence, correspondence is what defines truth. “…a belief is true when it corresponds to a certain associated complex.” It can be notice that truth is a characteristic of a belief that is not created by the mind, but rather is produced by the relation of the object of the proposition with the belief itself. When we say that the “grass is green” is true is because there is a successful relation between the statement and the fact that the grass is actually green. This is approved by the specific set of sense perception by a specific set of perceivers. Thus, Russell defends the idea of truth as something reachable and as a platonic idea within human beings. He raises the idea that the philosopher’s main activity is the one of criticizing. In fact, the philosopher must see the fallacies in all those beliefs that are taken as truths.

3. In contrast, there are some other philosophers who deny the attainability of truth or even the existence of it. An example of the latter is Friedrich Nietzsche. He introduced the concept of “historicity” and the “method of genealogy” in philosophy. This consisted in a revaluation of the concept of truth. He denied the importance of truth in contrast with appearance, and stated that truth did not exist. Not even logic can assure us of the existence of truth, but only can “...demonstrate its utility in regard to life…” We cannot make eternal statements from our position as human beings. He says that what we are most certain of is of our erroneousness as philosophers. For that reason, Nietzsche says that what is important and what human beings can only do is to interpret reality. His idea of will to power, or will to life, enables him to create what he calls “prospectus” , therefore the construction of knowledge based in an interpretative way with the aim of projecting ourselves into reality. Human beings are the ones who create values and, in this case, what can be true. A clarification must be made, even if Nietzsche rejects truth, this doesn’t mean that he denies the usefulness of justification. Indeed, justification is the necessary mean to achieve this projection of oneself into reality.

4. Another philosophy that denies the absolute value of truth is the one of pragmatism. Pragmatists see a distinction between the concept of truth and the concept of justification, and give priority to the latter since is the way a philosopher creates its own standpoint. According to this theory, there are many ways to justify an object of knowledge, and we use the way that is more useful and epistemologically productive. Consequently, the idea of truth becomes something unreachable, since, as Richard Rorty states: “There would only be a ‘higher’ aim of inquiry called ‘truth’ if there were such a thing as ultimate justification…” Truth is the eternal and absolute justification of an object of knowledge. Therefore, philosophers are limited to work only with justification. The absoluteness of truth is rejected and in its place comes a relation of “trueness” based on the relationship of the object of knowledge and the practical effectiveness of the belief to represent the object. In pragmatism, truth is not absolute, and hence, it is a human invention to explain reality in an effective way. Thus, philosophers are in a position where they have to create new effective justifications, rather than searching for a truth that is unreachable. is the human beings who create values and, in this case what can be true.

SOME FINAL REMARKS

We have seen in the previous three approaches to the problem of whether truth can be interpreted as an existent and coherent concept or not. What is more important to evidence is that there is a call for a common ground in the three different philosophies and this is the necessity of justifying beliefs; of justification itself. Truth may be attainable or not, but we cannot do philosophy without supporting our ideas with a logical and effective justification. On the other hand, we must take into account the fact that this justification is limited. No matter from which point of view we are looking at the nature of truth we see the incompleteness of the own theory to understand everything. We cannot conceive anything that is beyond the epistemic structure, or explain the “nature” of an object of knowledge, nor go beyond interpretation to a more objectified view of reality. Trueness as a value of statements comes with an efficient justification that takes specific objects of knowledge.

Concluding, justification becomes the important side of philosophy and is what will determine the knowledge about reality, as pragmatists say. This justification, on the other hand, is determined by the discourse in which the knowledge is argued. The justification must be based on some ground, and this base is the epistemological discourse around the specific knowledge that is being tried to put forward. Therefore, criticism becomes a central activity of the philosopher. It is what evidences the fallacies inside the justification and inside the same epistemic discourse were it arises. Thus, criticism and justification become integral, dialectic and even symbiotic within themselves. Criticism as the art of destroying knowledge and justification as the art of building it.

Bibliography

o Wartenberg, Thomas. "Hegel's idealism: The logic of conceptuality." The Cambridge Companion to Hegel. Ed. Frederick C. Beiser. USA: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

o Russell, Bertrand, The Problems of Philosophy, Great Britain, Oxford University Press, 1980

o Deleuze, Gilles, The Logic of Sense, Great Britain, Columbia University Press, 2010

o Nietzsche, Friedrich, La Volontá di Potenza, Milano, Italy, RCS Libri, 2008

o Rorty, Richard, Philosophy and Social Hope, Penguin Group, England 1999

Topic: On the incompleteness of philosophical knowledge and the idea of truth: criticisms and justifications

No se encontraron comentarios.